Lucian Freuds

From Out of a Featureless Crowd

By KAREN WILKIN

New York

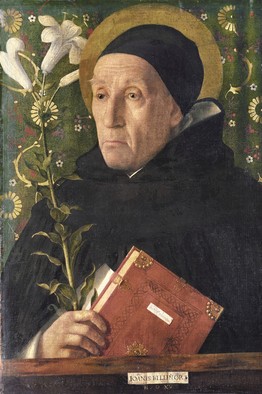

‘Fra Teodoro of Urbino as St. Dominic’ (1515), by Giovanni Bellini.

Portraits, from gritty Lucian Freuds to the fatuous kitsch perpetrated by street artists, are such a constant presence in our visual landscape that it’s hard to remember that the genre’s history is far from continuous. For centuries, throughout the ancient world—in Mesopotamia, Egypt and Greece—human beings were depicted according to strict, near-abstract conventions, except for a short-lived period of relative naturalism during the reign of the renegade monotheist pharaoh, Akhenaten. The Romans, of course, excelled at memorial portraits, sculpting heads uncannily like people we still encounter on present-day Italian streets and, in the further reaches of the Empire, painting those astonishing, liquid-eyed face-panels for Roman-era Egyptian mummies.

Medieval manuscripts sometimes include images of donors, but essentially as emblems of kingship or duchesshood rather than as reports on the particularities of recognizable persons. Aristocrats, in the Middle Ages, are depicted no more specifically than peasants performing labors appropriate to the seasons; they’re just better dressed. It’s not until the Renaissance that we again find representations as sharply characterized as those of ancient Rome, evidence not only of what the 19th-century Swiss cultural historian Jacob Burckhardt called “the revival of antiquity,” in his seminal work “The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy,” but also of, in Burckhardt’s terms, “the development of the individual” and “the awakening of personality.”

These new attitudes come to life in the delectable survey “The Renaissance Portrait: From Donatello to Bellini,” a collaboration between the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. More than 150 paintings, sculptures, reliefs and drawings trace the development of the likeness, mainly during the 15th century, from stylized profile images, inspired by antique medals, to three-quarter views of convincing personages who turn easily in space and coolly appraise us. It’s a stunning show, with a checklist that reads like the iconic collection of an ideal museum of the quattrocento, plus compelling works by less familiar Italian artists and a few splendid Netherlandish portraits for comparison.

The Renaissance Portrait From Donatello to Bellini

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Through March 18

Organized both chronologically and thematically, the exhibition begins with a Donatello “speaking reliquary” (c. 1425): a gilded bronze bust designed to house a skull fragment of St. Rossore, the image denoting the type of relic enclosed. Somehow, Donatello transforms a traditional devotional form into a potent evocation of an individual, pointing the way to the vividly personal paintings and sculptures of demure women and powerful men in subsequent galleries.

The Donatello bust is accompanied by early quattrocento paintings of male profiles by Masaccio, Paolo Uccello and (probably) Domenico Veneziano, all of them with red cappucci—long-tailed hoods—piled on their heads. Despite their robust modeling, they seem schematic, as do many of the images of young blondes that follow, paintings by such masters as Filippo Lippi, Sandro Botticelli and the Pollaiuolo brothers, and suave marble busts by Desiderio da Settignano and Andrea del Verrocchio. So it’s no surprise to learn that the men may be posthumous portraits, made as symbols as much as truthful likenesses, or that the women, with their elaborate hairstyles, opulent jewelry and piquant profiles, are better interpreted as idealized embodiments of modesty and chastity than as accurate records of particular people.

Yet as we move through the exhibition, we are increasingly surrounded by specific individuals with particular attributes. Portraits of the Medici and their associates announce what Burckhardt called “the modern idea of fame,” a concept further explored, later on, in medals, busts, drawings and paintings of assorted (mostly male) notables, from clerics to humanist poets to merchants. Some are corpulent and jowly, others are lean and bony, still others have impressive noses or stubborn chins; all have had their most distinctive features emphasized, as if to ensure immediate recognition or confirm relationships. We note, for example, the long, narrow d’Este face, captured by Pisanello in his portraits of Leonello, the marquess of Ferrara, in a Rogier van der Weyden portrait of Leonello’s “natural son.” We see how the erudite, hard-bitten humanist-warrior-duke of Urbino, Federigo da Montefeltro, and his small, blond son Guidalbaldo share an overbite and a sturdy chin.

The Medici section includes multiple versions of Botticelli’s commemorative portrait of Giuliano de’ Medici, Lorenzo il Magnifico’s brother, murdered in 1478 in the “Pazzi Conspiracy.” Supporters of the family commissioned images of the long-nosed, dark-haired young man with downcast eyes as signs of solidarity and loyalty. Lorenzo himself appears many times, in different mediums, most unforgettably in a fierce death mask. (The identification of the subject of a fresh little drawing by Leonardo da Vinci is disputed.)

We can learn a lot about the conventions and the development of Renaissance portraiture from this absorbing exhibition. We can compare drawings, sometimes made from life, with finished paintings or medallions. We can measure Benedetto da Maiano’s preparatory terra-cotta bust of the tough-minded Florentine banker Filippo Strozzi against the finished marble version (both 1475). Mostly, we can revel in such superb works as Giovanni Bellini’s 1515 “Fra Teodoro of Urbino as St. Dominic,” a sympathetic portrait of an elderly ascetic, holding a lily, that prefigures the entire Pre-Raphaelite movement. There’s Antonello da Messina’s skeptical young man with thick curling hair and a black cappuccio (1478) and Laurana’s nuanced marble of the introspective bluestocking Beatrice of Aragon (c. 1474-75). And much more. These glimpses into history, these interesting faces, gorgeous clothes and richly worked jewelry, come to us via incisive drawing, subtle modeling, glorious color and seductive surfaces. That’s a lot.

Ms. Wilkin writes about art for the Journal.

Copyright 2011 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved