Picasso Sculpture

EVANSVILLE, Ind.–A call from a New York art dealer about a glass sculpture by Pablo Picasso to a museum in Evansville, Ind., led the museum to search its holdings and unravel a bizarre mystery of a hidden treasure.

•By Michael Wheatley, Evansville Museum of Arts, History and Science

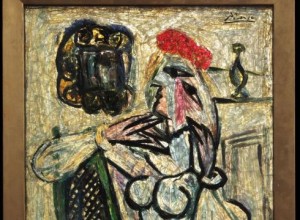

Pablo Picasso’s Seated Woman with Red Hat, a fired-glass piece kept in storage nearly 50 years, was only recently discovered to be genuine.

By Michael Wheatley, Evansville Museum of Arts, History and Science

Pablo Picasso’s Seated Woman with Red Hat, a fired-glass piece kept in storage nearly 50 years, was only recently discovered to be genuine.

Arlan Ettinger, of the art broker/auctioneer Guernsey’s, who had handled the sale of Jackie Kennedy’s possessions and Princess Diana’s things, among other celebrities’ belongings, was the New Yorker. In February, he was researching rare, extremely valuable sculptures made of glass — the word for it is “gemmaux” — by Picasso. One of Ettinger’s clients was considering selling some Picassos and was interested in their value. Ettinger tracked one to Evansville by perusing the papers of its original owner.

But old records of transactions involving art aren’t always reliable. Ettinger hung up the phone figuring he’d reached a dead end.

In Evansville, the museum staffers, their curiosity piqued, soon were rummaging through their storage area. And inside a shipping crate that had arrived during the tail end of the Lyndon Johnson administration, there it was, 3 feet tall, a couple of feet across: Picasso’s “Femme Assise au Chapeau Rouge” (“Seated Woman with Red Hat”).

“I pretty much know the lay of the land here,” said John Streetman, in his 38th year as the museum’s executive director, “but this was a total surprise.”

The cash value of such a piece can’t be known until it’s sold, but Ettinger puts it “in the range of $30 (million) or $40 million.” Another Gemmaux expert said that estimate sounds high. But even half as much is a lot of money to Evansville’s museum, whose entire endowment fund contains $6 million.

When Streetman got Ettinger on the phone with news of the Picasso’s discovery, “you could almost hear champagne corks popping in the background,” Ettinger said. “They were shocked. I don’t know if ’embarrassed’ is the right word, but maybe ‘amazed,’ ‘thrilled.’ ”

Museum officials, like the occasional lottery winner that doesn’t come forward right away, moved forward with caution. They debated what to do with their new-found masterpiece but kept the debate within the museum’s walls.

By the time they spilled the beans in August, their plan was in place: “De-accession.” That’s museum-speak for: sell the piece, take the cash. Guernsey’s Ettinger will handle the transaction via a private sale, not an auction. He said he has fielded some inquiries, but so far there’s no deal.

Evansville’s Picasso is surely the most spectacular artwork to ever come through town. But only a handful of museum insiders got so much as a peek at it. There was no public showing; the piece was not made available for media photographing. It may even be out of town already. All anyone in the know would say about the artwork is, “It’s in a secure place.”

“I wanted to show it,” said Streetman, “but the president of our board came up with a list of good reasons not to.”

Board President Steve Krohn is a businessman, a lawyer. “It would have cost too much money to insure and to adequately protect,” he said. “We might have had to hire additional security and make changes to the physical plant that we couldn’t justify for one item. We made the only prudent decision.”

A Studebaker — and a showman

The story of “Femme Assise au Chapeau Rouge” begins in 1954 with the great Picasso traveling to Paris and producing several dozen glass sculptures, or les gemmaux, in a new and original way.

In 1957, a collection of gemmaux was shown in Paris and New York, and some very fancy people made purchases, including Nelson Rockefeller, the emperor of Japan and Raymond Loewy. Loewy picked out “Femme Assise au Chapeau Rouge.”

Loewy today is largely forgotten. But back then, “the father of industrial design” was a ubiquitous celebrity. He designed locomotives, airplanes, tractors, the Lucky Strike cigarette package, the Schick electric razor, the Electrolux refrigerator and the Greyhound Scenicruiser.

Loewy liked to mingle with artists. He counted Salvador Dali a close friend. He collected art and gave it away.

In 1963, as the South Bend, Ind.-based carmaker Studebaker basked in the accolades for the look of its radical, grilleless, Loewy-designed Avanti sports car, Loewy agreed to give his Picasso to the Evansville museum.

Loewy died in 1986, but the decision makes no sense to his son-in-law, David Hagerman, who lives in Atlanta and manages the Loewy estate.

“Raymond Loewy had a great affinity for South Bend,” Hagerman said, referring to the Studebaker connection. “I would have assumed if he’d have donated to a museum in Indiana, he’d have donated to a museum in the South Bend area.”

It’s possible Loewy never even set foot in Evansville, which is 300 miles from South Bend. But he did know Siegfried R. Weng, an artist and arts administrator who by all accounts was difficult to resist.

In the 1940s, Weng headed the art museum in Dayton, Ohio, where he curated a show of Loewy’s art collection and probably got to know the great designer.

Weng moved to Evansville to run the museum in 1950 and took the organization to new heights, leading it to the construction of its first new museum building.

“Siegfried (Weng) was like P.T. Barnum,” said Streetman. “A very unusual, wonderful man.”

Philanthropists often make donations based on personal relations, which would explain Loewy’s gift to Evansville. It’s impossible to know for certain how that gift came to languish in storage for 44 years. But it’s obvious that when Loewy’s Picasso arrived, the Evansville museum wasn’t paying attention. A staffer mislabeled it a work by “Gemmaux,” said Mary Bowers, the current curator.

Some possible explanations for the mix-up: The piece arrived in 1968 (per the terms of Loewy’s 1963 promise) just as Weng was retiring; the director as well as his staff may have been preoccupied with their own futures.

Besides, the piece itself wasn’t the colossus it is today. Its appraised value, for Loewy’s tax purposes, was just $20,000.

The value has increased considerably, but exactly how much isn’t clear because as far as the art world knows, no similar work has changed hands for many years.

“There’s no pre-established market,” said Tina Oldknow, curator of modern glass at the Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, N.Y., which owns three Picasso gemmaux pieces. “We received them in the ’90s, when no one really knew what they were,” Oldknow said. (She declined to disclose their appraised value.). “But now there’s an intense interest in the ’50s, and everything from then is being re-evaluated.”

Oldknow said she’d “rather not comment” on Ettinger’s estimate, “but I think it’s high.”

Just what will the Evansville museum do with its windfall? There are no plans.

“We’ll turn it over to the Finance Committee for their recommendations,” said Krohn, the lawyer.

Some townsfolk are sorry to see the artwork go, even if they never saw it in the first place.

“Seems like if the museum needed the money that bad they should have looked through their basement sooner,” said Brent Carroll, who manages River City Pawn, where people swap treasures for cash daily. “Something that’s been there since ’68, to right away take it to where no one’s going to see it again? I’d say keep it and put it on display a year or two, then sell it. But that’s just me.” Indiana museum unravels mystery of Picasso sculpture