Ballesteros ‘Could Get Up and Down Out of a Garbage Can’

NY Times

By LARRY DORMAN

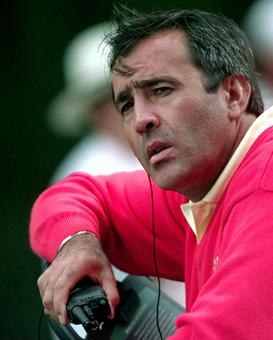

CHARLOTTE, N.C. — The reality of the death of the great golf champion Seve Ballesteros in Spain at the age of 54 dawned on the Quail Hollow Club on Saturday morning, its arrival fittingly wrapped in a thick fog that shrouded the golf course and delayed the start of play for 90 minutes.

Early arrivals were greeted by somber images on big-screen televisions beamed from the Spanish Open, where players wearing black ribbons on their caps stood in a light rain for a moment of silence to remember the man whose fiery passion changed the way golf was perceived and played.

At the tournament where Ballesteros began his professional career in 1976 and had his final European Tour victory in 1995, José María Olazábal wept on the shoulder of his countryman Miguel Ángel Jiménez.

Those two golfers, and 30-year-old Sergio García, who is playing at the Wells Fargo Championship here, are the three most prominent Spaniards to have been influenced by Ballesteros.

Untold thousands more who took up the game, in Spain and across Europe, Australia, South Africa, the United States and South America, were influenced by Ballesteros’s astounding artistry with a golf club.

Players whose styles differ greatly from the free-form, slashing style used by Ballesteros, like Davis Love with his powerful textbook action, are among the professionals who took something from Ballesteros.

Phil Mickelson, an imaginative feel player whose short-game genius can be mentioned in the same sentence as Ballesteros’s, was inspired by the way the long-armed Spaniard approached trouble shots in the trees and tight lies around the greens.

When asked if he tried to emulate Ballesteros’s full swing, Mickelson smiled.

“Maybe,” he said, “but not consciously. Although I do seem to find myself in some of the same kind of places.”

Meaning the trees, the rough and a variety of locations other than the fairway. More than anything else, those may be the most indelible memories Ballesteros created.

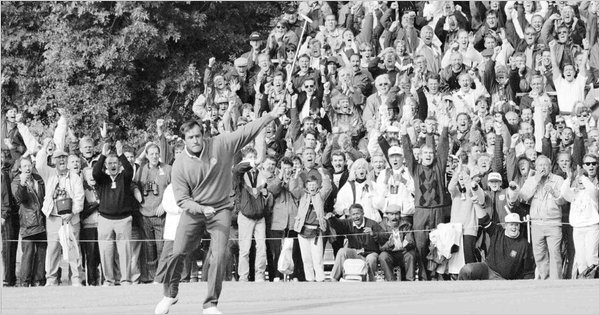

Yes, he was largely responsible for breathing life into the Ryder Cup after his arrival in 1979 created a renewed interest in a competition that had devolved into lopsided United States thrashings of teams composed of players from Britain.

And, yes, he made some waves with his gamesmanship in match play and ruffled feathers at PGA Tour headquarters with his stubborn insistence in 1985 that he would not play on the tour unless the minimum requirement of playing 15 events was waived for him.

Those memories are overwhelmed by the image of his standing in a field well to the left of the fairway in 1979, trying to find a way to win his first British Open. It was among the first memories recalled by Jack Nicklaus, who with 18 major championships is still regarded as the game’s greatest player.

“He was able to create shots, invent shots and play shots from anywhere,” Nicklaus said. “When he won at Royal Lytham in 1979, he played the 16th hole from a parking lot. I have watched him play 1-irons out of greenside bunkers, when just fooling around. He could get up and down out of a garbage can. He could do anything with a golf club and a golf ball.”

The renowned instructor Butch Harmon knew that side of Ballesteros well. He spent two weeks in 1995 at the Ballesteros family home in Pedreña trying to help him restore his natural method of swinging. It had become “too robotic” after Ballesteros sought help from instructors too numerous to mention.

“He had an unusual style of swinging the golf club,” Harmon said Saturday. “He had an unusual body. His arms were longer than most people’s his height. Most people don’t realize his right arm was longer than his left arm, so his swing was built around the length of his arms and his torso.”

“The thing that was phenomenal about Severiano Ballesteros was his imagination and creativity,” Harmon added. “He saw things that other players don’t see. He saw shots they don’t see. He was just a genius. He was like watching an artist paint a picture when you’d see him in the trees. I think he was more at home in the trees than in the middle of the fairway. The more trouble he got into, the more comfortable he felt in the situation.”

Remarkably, this style of play led to five victories in major championships, 45 other titles on the European Tour and four more in America, where his appearances were all too few.

In the Ryder Cup, in which he was magnificent, he and Olazábal combined for a record of 11-2-2, the best in the history of the event. His individual record was 20-12-5.

But to try to tell the story of Severiano Ballesteros with numbers is like trying to describe the Michelangelo’s Pietà by quoting its dimensions.

To Nick Faldo, the great English player and current CBS-TV commentator, Ballesteros was “Cirque du Soleil” for his stylistic and athletic interpretative abilities.

“For golf, he was the greatest show on earth,” Faldo said. “I was a fan and so fortunate I had front-row seat.”

To the Hall of Famer and world-class chipper Raymond Floyd, Ballesteros surpassed anything he could imagine.

“He was the most creative player in and around the golf course that I’ve ever seen,” Floyd said in a Golf Channel interview broadcast Saturday. “I used to think I was creative, but what he did pretty much defied description. That is how Seve will be remembered by the people who knew him, for that and the generous spirit that went unseen even by his fans.”

Late in his career, after signing an endorsement agreement with Callaway Golf, Ballesteros was having dinner with Ely Callaway, the company’s founder and chief executive, at a restaurant in Augusta, Ga. The night was filled with laughter, stories and toasts with Ballesteros’s favorite wine, the Spanish Rioja Marqués de Riscal.

As the night was ending, Ballesteros stood and, with tears in his eyes, thanked Callaway for believing in him. He had, he said, thought long and hard about what he could give Callaway. He wanted a gift “which I valued very much.”

At that, he peeled off the vintage Rolex watch he had worn since he first signed with the watchmaker more than two decades before and handed it to Callaway. Both men cried, raising their glasses.

Obituary, Page A20.

A version of this article appeared in print on May 8, 2011, on page SP10 of the New York edition with the headline: ‘He Could Get Up and Down Out of a Garbage Can’.