Tropical Diseases and the Construction of the Panama Canal, 1904–1914

The Mosquito: Its Relation to Disease and Its Extermination. From the holdings of Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine—Harvard Medical School.

The Mosquito: Its Relation to Disease and Its Extermination. From the holdings of Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine—Harvard Medical School.

The Hay–Bunau–Varilla Treaty of 1903 created the Panama Canal Zone and allowed the US government to begin building its 51–mile waterway through the Isthmus of Panama in May 1904. The transoceanic waterway opened in 1914, approximately four centuries after Charles I, King of Spain, conceived of a waterway across the Isthmus to facilitate Spain’s colonial interests in the New World.

In constructing the Panama Canal, American planners and builders faced challenges that went far beyond politics and engineering. The deadly endemic diseases of yellow fever and malaria were dangerous obstacles that had already defeated French efforts to construct a Panama Canal in the 1880s. The crippling effects of these diseases, which incapacitated many workers and caused at least 20,000 to die, led the French to abandon their goal in 1889.

For the later American effort, William Crawford Gorgas was appointed chief sanitary officer. His task was to prevent yellow fever and malaria infection among the laborers—a task that proved critical to American success.

The successful completion of the Panama Canal was a tribute to its organizers and specialists, among them Gorgas, whose highly effective sanitation measures eliminated the lethal or debilitating effects of yellow fever and malaria among workers.

Epidemiology of Yellow Fever and Malaria

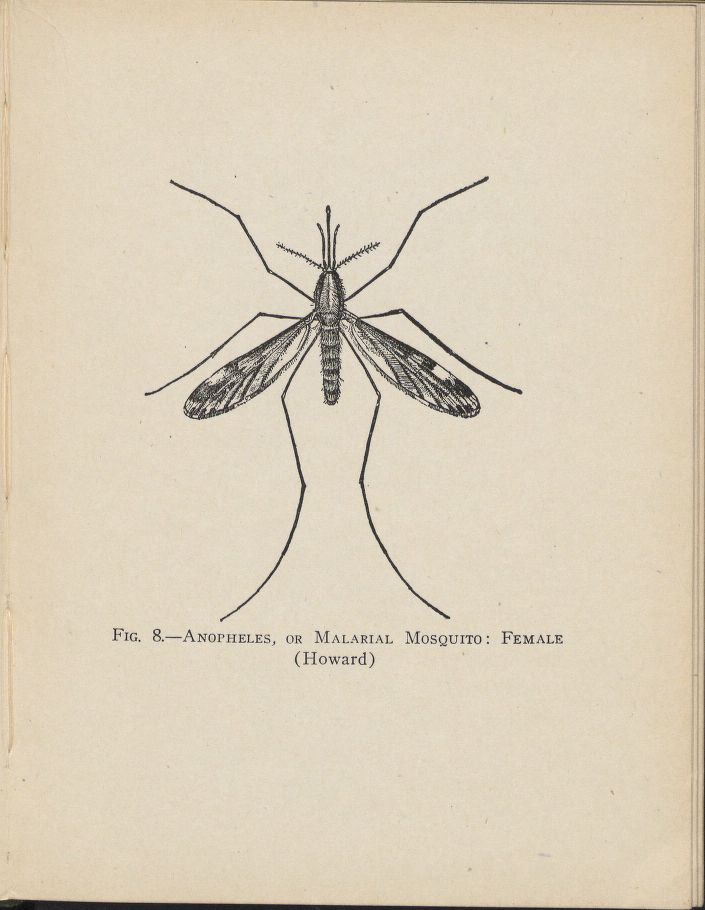

By 1904, medical researchers had established that yellow fever and malaria were mosquito-borne diseases. In Cuba, the Walter Reed Commission confirmed Carlos Finlay’s hypothesis and proved that the mosquito of the genus Aedes transmits yellow fever. As for malaria, the cumulative investigations of Charles Louise Alphonse Laveran, Ronald Ross, and Giovanni Battista Grassi and his collaborators proved that the female Anopheles mosquito transmits the disease–causing parasite.

By applying the results of these epidemiological studies to his sanitation methods, Gorgas prevented yellow fever and contained malaria among workers. Building on the sanitation methods he had pioneered in Cuba’s disease-stricken capital, Havana, in 1898, Gorgas developed a formidable repertoire of measures against mosquitoes.

The Results of Gorgas’s Sanitation Measures

Gorgas’s success in Panama was as dramatic as in Cuba: by 1906, he eradicated yellow fever and contained malaria during the canal’s 10-year construction period. Gorgas’s sanitary workers drained, or covered with kerosene, all sources of standing water to prevent mosquitoes from laying their eggs and larvae from developing; fumigated areas infested with adult mosquitoes; isolated disease-stricken patients with screening and netting; and constructed quarantine facilities. In major urban centers, new domestic water systems provided running water to residents, thereby eliminating the need for collecting rain water in barrels, which had provided perfect breeding sites for mosquitoes carrying yellow fever.

The US government’s $20 million investment in the sanitation program also provided free medical care and burial services to thousands of employees. In addition, Gorgas’s sanitation department dispensed approximately one ton of prophylactic quinine each year at 21 dispensaries along the Panama Canal route and added hospital cars to trains that crossed the Isthmus. Each year, hospitals treated approximately 32,000 workers, and 6,000 were treated in sick camps.

Selected Contagion Resources

This is a partial list of digitized materials available in Contagion: Historical Views of Diseases and Epidemics. For additional materials on the topic “Tropical Diseases and the Construction of the Panama Canal, 1904–1914” click here or search the collection’s Catalog and Full Text databases.